CIPSRT COVID-19 Readiness Resource Project (CRRP)

How To Identify and Manage Stress

- Taking Care of Your Basic Needs

- Types of Stress Faced by Public Safety Personnel

- Moral injury: What is it and Why Should I Care?

- Practical Ways to Reduce the Spread of COVID-19

- CRRP Virtual Town Hall Series

- Talking About COVID-19: Tips for Constructive Conversations

- Leading Through a Crisis: Tips for Public Safety Leaders

- Dealing With Financial Concerns

- More Information About COVID-19

- Acknowledgements

What is mental health?

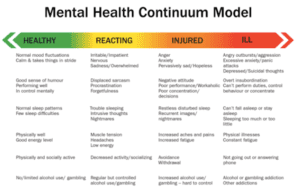

According to the World Health Organization, being mentally healthy means being able to realize your own potential, cope with normal stresses of life, work productively, and contribute to your community. Many factors can affect your mental health, moving you along a continuum that ranges from “healthy” to “ill”, as shown below:

As you move back and forth along the continuum, you may see differences in the way you act, think, and feel.

This continuum forms the basis for the Canadian Armed Forces’ Road to Mental Readiness (R2MR) mental health resiliency program. It uses an easy-to-read continuum that can help you gauge your current mental health, recognize changes in your mental health, and identify actions you can take to move back toward the “healthy” end. It has been adapted for use in many settings, including the U.S. Navy SEALs and the Mental Health Commission of Canada.

How does stress affect mental health?

Stress is a normal part of life. It is the pressure to respond to a variety of situations — and can help you meet deadlines, be productive, and try your best. But when stress is ongoing with no break, the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health warns it can become chronic or cumulative. At that point, stress can provoke a number of physical and psychological symptoms, especially when events appear to be dangerous or threatening.

The COVID-19 pandemic may be an especially stressful time for you and other PSPs because of the uniquely vulnerable position you are in. The occupational demands of your job require you to act against the safety recommendations of public health officials. This places you at greater risk and may leave you worried about bringing the virus home to your family or being asked questions about the pandemic you can’t answer.

Added and prolonged stress can affect your thinking, emotions, behaviour, and body. Its specific effect on you depends on many factors, including pre-existing mental health conditions, the availability of resources, past experiences, and social and economic circumstances.

Common reactions to stress include changes to your arousal level or your level of engagement with the world around you. Hyperarousal (the fight-or-flight response) puts your body on high alert and ready for action, leaving you with muscle tension and making you more irritable and impulsive. Hypoarousal produces the opposite effect, leaving you emotionally detached and feeling unable to move or do anything.

In either case, your body may use significant energy resources to deal with stress, diverting them away from essential bodily functions like rest, digestion, and immune function. Other symptoms of excessive stress may include:

- Difficulty concentrating

- Irritability

- Interference with daily tasks

- Restlessness

- Changes in appetite and sleep patterns

- Decreased motivation and energy

- Persistent negative thoughts

- Muscle tension

How much stress is too much?

Although it’s normal to feel a bit anxious, stressed, or overwhelmed during this time, it’s important to recognize when those feelings start to negatively affect your life so you can develop coping strategies to stay balanced. If you find yourself so consumed by the need for information about the virus that you can’t concentrate on anything else or feel like you’re shutting down, these may be signs that your usual coping strategies aren’t enough. Other signs could include having more extreme physical or emotional reactions, or just not feeling like yourself. In these cases, it may be time to seek additional support.

Try reaching out to a friend, trusted colleague, or family member. Talking to your supports lets you express how you’re feeling and validate the impact of what you’re going through, and they may be able to suggest new coping strategies. If informal support from your network doesn’t improve how you’re feeling, seek out formal supports and services such as mental health professionals, formal peer support programs, chaplains, or employee assistance programs.

The COVID-19 Readiness Resource Project (CRRP) features several virtual town halls that discuss ways to manage stress:

- Coping with the Stress of COVID-19 for Public Safety Personnel with Dr. Jeff Sych, Angie Boucher, Christine Godin, Lt. Scott Patey, Sgt. Joy Prince, and Meghan Provost

“Coping With Stress” Town Hall

- The Unique Nature of Stress in Public Safety Personnel with Dr. Jeff Sych, Assistant Chief Jason Bowen, Jason Shaw, and Jennifer Wood

[EMBED VIDEO OF “UNIQUE NATURE OF STRESS” TOWN HALL]

- Self-care During Times of Crisis and Change with Meghan Provost, Nathalie Dufresne-Meek, Katherine Belhumeur, Richard Doyle, and Drs. Alexandra Heber and Rose Ricciardelli, plus a special message from Commissioner Anne Kelly to members of the Correctional Service of Canada

“Self Care During Times of Crisis and Change” Town Hall

Where to get help

If you don’t already have access to support or don’t feel comfortable reaching out through your employer, the resources below can assist and provide information on what is available locally.

Crisis Services Canada

If you are in crisis and need help:

- Visit Crisis Services Canada’s website

- Call 1-833-456-4566 (available 24/7)

- Text “Start” to 45645 (available 4:00 to midnight ET)

Canadian Psychological Association

- Find a psychologist near you.

- The CPA also maintains a list of psychologists who have volunteered to provide psychological services for front-line healthcare providers.

Daily mindfulness sessions with psychiatrists

You can join a free online mindfulness session every Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday at 8:00 p.m. ET. Drop in and learn short mindfulness practices to help you find calm during this challenging time. Optional discussion will follow each session. Contact the day’s facilitator for more information or just join the Zoom meeting using the links below. (Note: This is not treatment or therapy.)

- Mondays: Dr. Diane Meschino

Meschino@wchospital.ca

Zoom: https://zoom.us/j/6132246869, Meeting ID: 613 224 6869 - Tuesdays: Dr. Jennifer Hirsh

hirsch@sinaihealth.ca

Zoom: https://zoom.us/j/148527614, Meeting ID: 148 527 614 - Wednesdays: Dr. Mary Elliott

Elliott@uhn.ca

Zoom: https://zoom.us/j/9482159624, Meeting ID: 948 215 9624 - Thursdays: Dr. Orit Zamir

Zamir@sinaihealth.ca

Zoom: https://zoom.us/j/302330041, Meeting ID: 302 330 041

Other resources to support mental health during COVID-19

- Mental and Physical Health (Veterans Affairs Canada)

- Anxiety Canada

- Big White Wall

- Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction

- Canadian Mental Health Association

- Centre for Addiction and Mental Health

- Department of National Defence

- LifeSpeak blog

- Mental Health Commission of Canada

- S. National Center for PTSD

- Wellness Together Canada